Claudia Burzichelli doesn’t want to die like her dad. Nine years ago, her father, already afflicted with Parkinson’s, killed himself with a gunshot to the head days after his release from a hospital where he had been treated for a heart attack.

Burzichelli, 54, now suffering from kidney and lung cancer, is haunted by her father’s violent death, even more so as she contemplates her own mortality. She hopes to find a more peaceful way to end her life, if it comes to that.

This article was published by Bloomberg News on April 11th, 2013. To see this article and other related articles on The Globe and Mail website, please click here

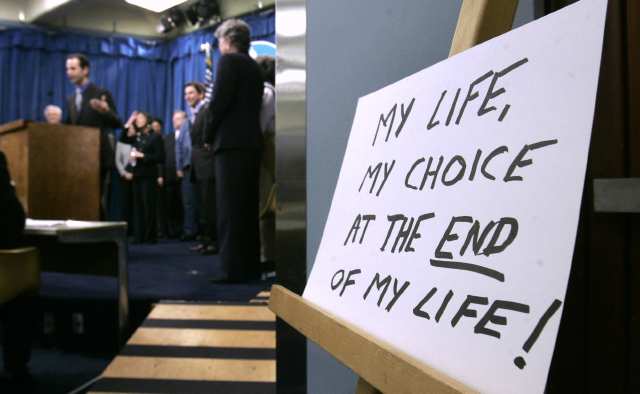

“On those days when I’ve struggled to breathe, when I think about the stresses on my family, I would hope that I might have more options than starving myself or taking my life in a violent way,” she told a panel of New Jersey lawmakers during a hearing in February on a bill to legalize assisted dying. “It comforts me to think there could be a process, a way to offer options that would not hurt my family.”

Baby boomers, like Burzichelli, a former education manager at Rutgers University, are at the forefront of a new movement. They brought on the sexual revolution, demanded natural childbirth, fought for legalized abortion and turned the mid- life crisis into a force for self-improvement. Now they’re engaged in transforming how Americans experience death.

In states across the country, including New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts and Vermont, graying baby boomers have been lobbying lawmakers in recent months at hearings, in letters and by phone, pushing to make it legal for doctors to prescribe life-ending drugs to terminally ill patients. Advocates and opponents say there is more support this year than in past attempts with five states considering such legislation.

Painful Deaths

A subject of intense debate since the 1990s, state- sanctioned and regulated end-of-life drugs are gaining support amid demographic changes and shifting attitudes. Baby boomers are beginning to confront their own mortality even as they face the sometimes prolonged and painful deaths of their parents — the first to die in an era of modern medical care that can keep death at bay for months, often at great expense, with feeding tubes, ventilators and defibrillators. About 10,000 baby boomers, those Americans born from 1946 to 1964, will turn 65 each day for the next 19 years, according to the Pew Research Center in Washington.

“The baby boomers are aging, and we all have witnessed or are about to witness the death of our parents or people very close to us,” said Barbara Coombs Lee, who runs the advocacy group Compassion & Choices, which lobbies for so-called aid-in- dying laws. “There is an attitude difference about the boomer generation. There is an expectation that we can be empowered and we can impact our fate.”

Milky Drink

Bills under consideration in northeastern states as well as in Kansas are modeled after laws in Washington and Oregon, the only two states that currently permit doctors to prescribe life- ending drugs. One of those, in New Jersey, is sponsored by Burzichelli’s brother-in-law, state assemblyman John Burzichelli. Often referred to as physician-assisted suicide or doctor-aided dying, the movement has come a long way from the 1990s when Jack Kevorkian, a Michigan pathologist, was in the spotlight for hooking patients up to a homemade device that helped them administer lethal drugs.

In Oregon and Washington today, patients wishing to end their life must go through a series of steps that can take over a month to complete. Two doctors must determine a patient has fewer than six months to live and is of sound mind to decide to take the drugs. If patients show signs of depression or dementia, they must be evaluated by a psychiatrist. Patients must be able to self-administer the drugs, which are mixed with water to become a milky drink. Minutes after the drugs are taken, the patient falls asleep and, within a few hours, dies.

College Educated

In Oregon, 77 were granted and took end-of-life drugs in 2012, less than 1 percent of all deaths, according to data from the Oregon Public Health Division. In Washington, which legalized the practice in 2008, the numbers are similar with 70 people dying in 2011 after ingesting the medicines, the state’s department of health said.

Though the numbers are small they offer a glimpse at the demographic and social forces that are combining to advance the end-of-life movement. In both states, those who chose to end their life with the aid of a doctor were predominately white, urban and college educated. The vast majority had cancer, 78 percent in Washington and 75 percent in Oregon, and in both states, more than 60 percent of people were 65 and older, according to state figures. The most common reasons cited for ending life in Washington were a loss of autonomy, dignity and the ability to participate in the things that make life enjoyable.

Unbearable Illness

“Most people we hear from are fairly well educated and they don’t like the choices available in the medical world,” said Judy Epstein, director of clinical services at Compassion & Choices, who oversees the Denver-based group’s volunteers and has been at several assisted deaths. “They are people who want to be proactive and want to ensure they will have a peaceful death on their own terms, that they won’t be in a hospital on a ventilator, that they won’t be knocked out on drugs or be in pain.”

The experience in Oregon and Washington has turned bioethicist Art Caplan, director of the division of bioethics at New York University, from a strong opponent of assisted suicide to a supporter. Before the law in Oregon was enacted, he feared there would be a flood of patients making snap decisions to end their life. Instead, Caplan said he has been shocked by how small the numbers have been and that most people are interested in having a death option in case their illness becomes unbearable. In Oregon last year, about a third of the patients who received a prescription for the drugs never took them.

‘Saving Lives’

“I opposed this because I thought people would kill themselves too quickly, that the poor would be shuffled over,” Caplan said. “It just didn’t happen.”

While Caplan has changed his views, opposition from doctors, religious organizations, anti-abortion groups and disability advocates hasn’t been swayed. They are waging their own campaigns at the state level against legalizing any form of aided dying.

The Washington, D.C.-based anti-abortion advocacy group National Right to Life takes the position that all life has value and the priority should also be trying to improve the quality of life for patients with terminal illness, said Jennifer Popik, legislative counsel for the organization. The group helps its state affiliates lobby against the measures.

“You don’t fix the problem by killing the patients,” Popik said. “We want the focus to be on saving as many lives as possible and having people’s quality of life be as high as it can be.”

Family Burdens

Patients with disabilities have also opposed the bills, showing up at state legislative hearings, including one last month in Connecticut. Diane Coleman, president of disability- rights group Not Dead Yet, based in Rochester, New York, said her group worries the laws could put pressure on disabled patients to end their lives when they feel they are becoming a burden on their families.

“I feel like there is a pressure being placed on folks against getting good health care when they have advanced conditions, as in we shouldn’t be wasting money on them,” Coleman said. “It is very much a concern that some people will feel pressure to end their life.”

Those fears have merit given the high cost of end-of-life treatment, said Tia Powell, director of the Montefiore Einstein Center for Bioethics in New York. Powell said she doesn’t have a stance on the laws.

Medical Bills

“One of the major reasons for bankruptcy is medical bills and one thing you don’t want to do is tell people facing the end of their life, ‘could you hurry it up because the meter is running,’” Powell said. “The financial element to this is huge and you have to make sure you aren’t substituting this for appropriate care.”

A much bigger concern for most people, according to the data from Oregon and Washington, is losing their autonomy and dignity and ability to engage in activities they enjoy. Coleman said that wanting to die for those reasons is offensive to the disabled, many of who live for years without being able to walk, bathe or go to the bathroom on their own.

Hospice Care

The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, an Alexandria, Virginia-based group for hospices and their employees, said it opposes expanding the states where physicians-assisted dying is legal. The organization said many of the issues that cause people to want to end their lives, like concerns over pain or being a burden to their families, can be addressed by hospice care and counseling. They would like efforts to be focused on getting more terminally ill patients enrolled in hospice sooner and educating doctors about better pain management.

Burzichelli, who was the founder and executive director of the Center for Effective School Practices at Rutgers University before her illness required her to step down, worries hospice care may not always be enough, and she’s determined to prevent herself and others from facing a situation like her father’s. Her lung cancer, which is in the advanced stages, has been stable and she recently had one of her kidneys removed to try to stop the cancer’s spread. She says she’s trying to focus on life and the living. Still, Burzichelli would like the comfort of knowing she has options, including ending her life on her own terms.

“It is helpful to have a process where people are allowed to talk about that with their physicians, if what they are looking at is too bleak to deal with on their own,” she said in a telephone interview. “It would make a lot of people’s lives more peaceful.”