“Every man must do two things alone; he must do his own believing and his own dying.”

Nobody wants to talk about the taboo subject of end-of-life care. And yet, few things are more important to discuss with your doctor and your loved ones.

There is a valuable lesson to be learned from one of the most outrageous examples of mass hysteria recent history has to offer. In 2009, Americans were discussing President Obama’s (very sensible) plans for healthcare reform. The House Democrats’ Bill contained a section promoting advance care planning. It included fairly standard items such as information on living wills and durable powers of attorney. The idea was to allow everyone – young and old – to express clear wishes for end-of-life care and to take steps to ensure those wishes were respected, whatever they may be.

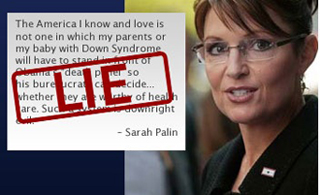

Meanwhile Governor Sarah Palin had resigned from office on July 3rd. For a little over a month, the previously ubiquitous Palin dropped off the front pages and the headline news. On August 7th, 2009, Palin posted an incendiary note to her Facebook page in which she expressed her opinions on the proposed reforms.

The note was a measly 318-word Facebook post. Though it was unconstrained by facts or supporting evidence it still had the unfortunate effect of framing the debate on healthcare reform in the months that followed. Referencing the advanced care planning provisions Palin wrote:

“Who will suffer the most when they ration care? The sick, the elderly, and the disabled, of course. The America I know and love is not one in which my parents or my baby with Down Syndrome will have to stand in front of Obama’s “death panel” so his bureaucrats can decide, based on a subjective judgment of their “level of productivity in society,” whether they are worthy of health care. Such a system is downright evil.”

When pressed for an explanation, Palin explicitly fingered section 1233 of the Bill, which sought to compensate physicians for providing voluntary counseling to Medicare patients about living wills, advance directives and end-of-life care options. To say that the provisions would lead to targeted euthanasia was an exceptionally ridiculous and misleading take on a section of the Bill that was so uncontroversial it had enjoyed widespread bi-partisan support. Furthermore, – the behind-the-scenes architect of the Bill was widely acknowledged to be Johnny Isakson, a pro-life Republican Senator from Georgia who had actively pushed the advanced care planning agenda and previously co-sponsored two similar Bills.

To put it mildly, it was preposterous and irresponsible to raise the spectre of Nazi Germany to contest what was indisputably good policy. The Democrats largely opted to dismiss the claim rather than take it seriously and address it. This turned out to be a mistake: months later, independent polls were confirming that 30% of Americans believed the “death panels” canard! AARP meetings became ground zero for the polarization in public opinion when it came to death panels. Some seniors were even seen holding Hitler placards and hurling insults at the moderators.

The Democrats failed to acknowledge that no matter how ridiculous the charge, it had hit a nerve of anxiety that played strongly with seniors because it was so close to home. People intuitively know that at the end of the day, healthcare reforms also aim to cut costs. This makes people nervous – especially seniors. They could imagine themselves begging for their lives in a resource-depleted system.

What better than fear and anger to turn normally polite, rational people into screaming heaps? And what is more fearsome and loathsome than suffering and death? Is it any wonder that when it comes to end-of-life care and the difficult discussions that come with the territory – many of us sensible, intelligent folk ignore the obvious until it’s too late?

We should never allow fear and panic to be our only guide while making decisions that ought to be made rationally. The American example can hopefully at least help shed some light on issues surrounding end-of-life care policy and serve as a cautionary tale. It seems abundantly clear that families, patients and doctors should be having these discussions before they find themselves in crisis.

Once they arrive in the I.C.U., or when they are first devastated by the news of a terrible diagnosis, patients are so overwhelmed with fear and anxiety that it becomes next to impossible to navigate the maze of medical possibilities while staying true to what they might ultimately want. Doctors are ill equipped to guide them through a process that one could argue is more delicate than surgery – and requires significantly different skills, rarely found in the same people.

It seems so obvious that we tend to forget that the conversations are not happening. A March 2012 Ipsos-Reid poll found that a startling 86% of Canadians have never even heard of advance care planning and that only 9% have ever spoken to a physician about their wishes for care in that regard. Being informed about these issues does not translate into an effective plan of action; surveys find that only 30% of Canadians who have thought about end-of-life care have actually discussed it with their physicians. Even though CARP members tend to be better informed than the general population about healthcare issues – they are no exception to the rule: the CARP poll on advanced directives produced similar findings.

But are Canadians able to access end-of-life/palliative care if they need it? Again, the answer may shock you: overwhelmingly, no. Only 16% to 30% of Canadians who die currently have access to or receive hospice palliative and end-of-life care. Our expansive landscape is speckled with many urban centres, but dominated by more sparsely populated areas – which accounts for significant variations in the availability of services from one region to another.

This is one of the reasons Canada ranked ninth in the Economist’s Intelligence Unit 2010 “Quality of Death” index. Despite our high rankings in providing for the availability of pain medication, we were criticized for forcing people and their families to shoulder a unreasonable part of the cost of home care and palliative care services. The Journal of Palliative medicine found that Canadian families absorb 25% of home care costs, which can often be astronomical. Unlike many other countries, we do not have a National Strategy on Palliative and End-of-Life care. As Dr. Jose Pereira, Medical Chief of Palliative Care at the Ottawa Hospital so eloquently put the case:

“Even Georgia, in the former Soviet Union, and Poland have national strategies. We also need a Secretariat to coordinate activities between government and community organizations. Canada once led the world in palliative care and is rapidly falling behind for lack of coordination and leadership.”

It is a curious thing to see ourselves from another’s perspective… odd and yet instructive. The Quality of Life index provided especially interesting commentary on one facet of the issue; they posited that death was more taboo in Canada than it was in Europe. The writers believed that we may be influenced by our American neighbours and their obsession with medical technology that sustains life without restoring health. The focus on sustaining medical life when we should be preparing a graceful exit is born of an intense desire for hope. But too often, it creates unnecessary suffering and makes death and bereavement more difficult for both patient and family.

Throughout history, with some notable exceptions, passing away has generally been the rapid result of nature’s progression. It would have been atypical for someone to require palliative care centuries ago because the interval between the recognition of life-threatening illness and death was typically a matter of days. The process was brief and people typically agreed on how to approach death. There was a concensus about customs surrounding the event – they were largely religious and prearranged.

The Ars moriendi (“The Art of Dying”) refers to two related Latin texts dating from 1415 and 1450 which explained the protocols and procedures to be followed in order to “die well” and in accordance with the Christian precepts of the middle ages. It was written within the historical context of the effects of the macabre horrors of the Black Death 60 years earlier and the consequent social upheavals of the 15th century. It was extraordinarily popular (it just may have been the Middle Age’s answer to the DaVinci Code!), translated into most Western European languages and reprinted in more than 100 editions across Europe.

Reaffirming one’s faith, repenting one’s sins, and letting go of one’s worldly possessions and desires were crucial elements, and the guides provided families with prayers and questions for the dying in order to put them in the right frame of mind during their final hours. Last words held a particular place of reverence.

Today, medical science has completely redefined the way we experienced death and the dying process. It affords us the ability to ward off death – but at what cost, not just financially but spiritually and physically? And is it all for naught?

We have read the reports and heard many individual stories and case studies. We have made some startling discoveries, which we will be happy to share with you in following installments of the “Time to Talk” series. For example: did you know that study after study has found that doctors who are intimately familiar with death tend to prefer withholding aggressive care when it is their own turn to die? Did you know that every single expert panel or committee report that has been written about end-of-life care has underlined the urgent need to create an palliative care secretariat, even though we already had one in existence between 2001 and 2006 (it was dissolved in 2007)?

These are among some of the many topics we will cover in the next few installments: we will discuss what is currently being done and what needs to happen from a policy perspective, we will lay out all the options, the terminology and explain what some of the end-of-life interventions might look like and help you access all of the best resources that are currently available.

The subject may be taboo, but the time has come for serious discussion on this very important issue to each and every one of us – whether for ourselves, or for our loved ones. Over the next few weeks and months, we will open up this complex issue for intelligent discussion among our members and resident experts.