I have a cousin who sends me interesting tidbits via the internet, knowing full well that I’d never find them on my own. Recently I was the delighted recipient of a You-Tube video featuring several little children, ranging from five to about 11 who were confronted with a mysterious object called a typewriter.

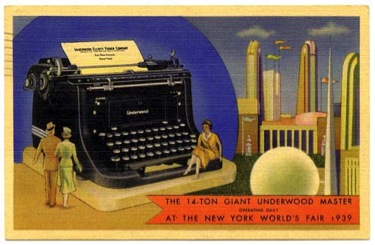

The reactions ranged from total puzzlement, to delight as they explored the intricacies of that object – the “writing machine”, which revolutionized written communication starting in the 1860’s. The Underwood I first did battle with sat in my father’s office and provided my first paid employment. While I have no way of knowing its vintage, I imagine it was purchased in the 1920s. To people who collect such items, the most valuable are those labeled No. 1 and No. 2, by the Wagner Typewriter Company. Invented by German-American Franz K. Wagner, the company was bought out by John T. Underwood. At first the Underwood Company manufactured carbon paper and ribbons. When Remington, who also made typewriters decided to make its own ribbons and carbon paper, Underwood is quoted as saying, “All right then, we’ll just build our own typewriter”.

Later Underwoods had the little see-saw button on the right that allowed the typist to switch from black ribbon to red. While you could run a ribbon back and forth to use many times, sooner later it would have to be changed, resulting in black and red smudges on fingers, faces and any other surface within reach, until you managed to slide it into a little U shape gadget with a mind of its own. I imagine ours was a No. 5, which became the iconic Underwood, probably manufactured between 1900 and 1931, and had probably sat on many other desks before arriving on my Dad’s.

I typed my father’s business letters – luckily they were short – from the time I was about 12, for the princely sum of 10 cents per letter, including carbon copy. This helped augment my finances, particularly in the summer, when les Canadiens did not play hockey therefore depriving me of any opportunity to collect on my standing ten cent bet with my Dad. As some might recall, I collected ten cents every time they won, plus the split in goals. Luckily they won frequently, although this was no help off-season. I do not know why I settled on ten cents a pop for everything, except for the fact that you could buy a two-scoop ice-cream for that princely sum, which was reason enough. According to the rate of inflation ten cents in 1940 would now be worth about $1.67. If anyone knows where to get a two-scoop ice cream for $1.67, please let me know. On the other hand, if I’d saved a 1940 Canadian George VI silver dime it could now be worth about $30. That’s lots of ice cream. Probably too much.

One of the reasons I needed to learn to type is that I decided early on that my ambition was to become a foreign correspondent. Alfred Hitchcock is to blame. In 1940 he produced a thriller which begins with actor Joel McCrae witnessing someone fall dramatically down a huge outdoor stairway in Amsterdam. I remember nothing else about the movie, but by looking it up I see that it had an absolutely stellar cast, including Herbert Marshall, George Sanders and Robert Benchley, and is replete with “Hitchcockian” intrigues and clever plotting. While I did actually make it to the sports desk of the Montreal Gazette, the farthest afield I was sent was probably Longueuil to cover a swimming meet, a distance of about five miles. This was hardly a world-shaking event, but – in truth – women weren’t entirely welcome in the newspaper business in those days, although the writers on the sports desk accepted my teen-aged presence with equanimity, helpful survival hints, and a strict prohibition of curse words.

I did try to bolster my image by trying to emulate movie stars of the day such as Rosalind Russell, who managed to type furiously on breaking news, with a lit cigarette hanging precariously out of the side of

her mouth. Typing furiously was attainable. However, inhaling cigarette smoke brought resulted in a round of gasping, wheezing, coughing and streaming eyes. I decided I would have to create my “girl reporter” image sans cigarette.

One of the elements of the old typewriters that intrigued the kids on the U-Tube segment was the “ding” when the typists came to the end of a line, and then you could fling back the carriage with the lever on the left. They thought that was great sport. They also realized that in years to come, their children will look back on the technology they are using now, as though they were examples of antiquity. They might even hear Leroy Anderson’s “The Typewriter Song” on the radio, and be the only ones to recognize that distinctive “ding”.

For the Leroy Anderson composition, see The Typewriter.